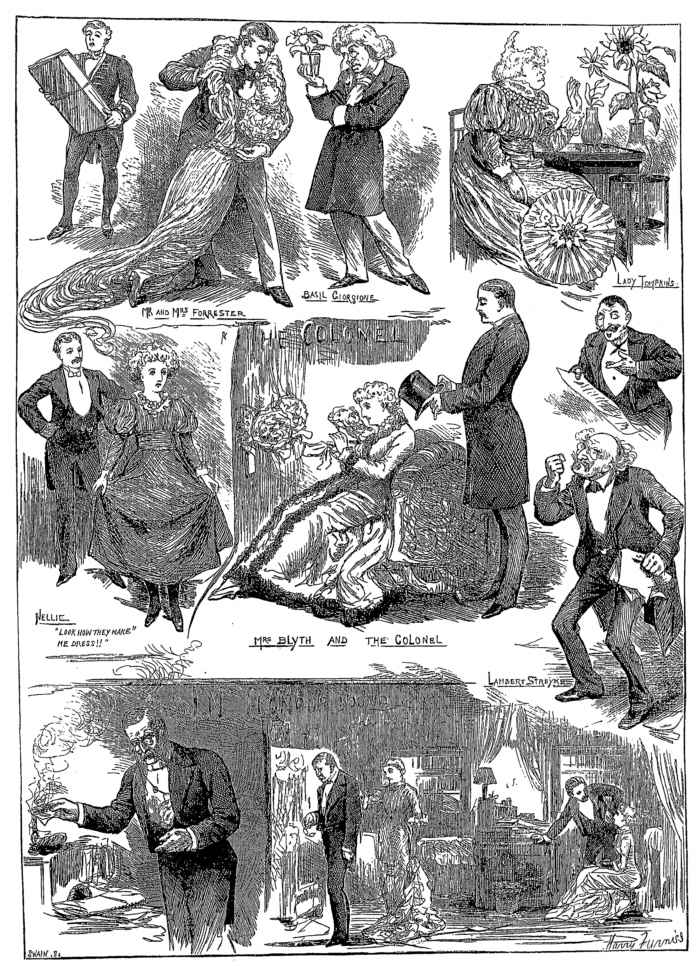

| THE COLONEL |

• Illustrated London News, 12 February 1881.

• Illustrated London News, 26 March 1881.

Sunday, 6 February 1881. Supplement,

AT THE PLAY.

A lively sally in Mr. Burnand’s good-humoured vein of burlesque is made in The Colonel at the expense of those who carry too far their devotion to art in daily life. The extravagances, or supposed extravagances, for the purposes of passing caricature – it really does not much matter which – of the æsthetic folk have, for a long time past, supplied material for the pen and pencil of the social artist. It might, indeed, have been thought that Punch had well nigh played the subject out, especially as most people know only by hearsay of the eccentric affectations so readily parodied and ridiculed. To Mr. Burnand, however, it has seemed otherwise; and whatever may be thought of the freshness of his fun in this, his latest production, there can certainly be no doubt that on Wednesday last it provoked plenty of merriment at the Prince of Wales’s Theatre. The new play is built on the lines of Le Mari à la Campagne, a comedy in which, as in its old version, The Serious Family, the excess and hypocrisy of religion are attacked. Those who remember Morris Barnett’s Haymarket play will perceive that the substitution of art for religion, in connection with the craze of a young wife and the boredom of a young husband, is one of Mr. Burnand’s characteristically happy thoughts. In discussing so slight a fabric as this it is hardly necessary to consider whether a Mr. Forrester would really be so far affected by the artistic tastes of his wife and his mother-in-law, Lady Tompkins, as to find his home unbearable, and to take refuge in the society of a gay widow, whom he visits en garçon and under an alias. At any rate, the leaders of the mutual admiration society gathered around them by Mrs. Forrester and Lady Tompkins are sufficiently offensive in appearance, manner, and self-assertive superiority to disgust any reasonable man. The only marvel, indeed, is that Mrs. Forrester, who is really fond of her husband, and shows herself when matters come to a crisis to be open to conviction, should tolerate such unpleasant impostors as Lambert Streyke and his nephew, Basil Giorgione. For it need scarcely be said that the apostle of “higher development” repeats the catchwords of his creed ad nauseam, and is himself so palpable a fraud that he could not well deceive any one, except a silly old woman like Lady Tompkins. That this should be so arranged is probably necessary in order to make the point of the joke go home to playgoers who would not appreciate the force of a more subtle attack upon the neophytes of the Grosvenor Gallery, and their “precious” method of revealing the “valuable” in art. As it is, the parody is entertaining, and where in the first act it shows a tendency to drag and repeat itself, the remedy is obvious and easy. The second act has for its scene a room decorated in such Philistine fashion as to contrast in the most forcible manner possible with the æsthetic apartment, in which lilies and sunflowers run impossible riot. We are not sure, however, whether Mrs. Blyth’s studiously common-place parlour would not please the really æsthetic eye more than the grotesque drawing-room supposed to be fitted up in accordance with the taste of the cult. Whatever the excesses of Mr. Burne Jones’s indiscreet followers may have been, their influence has as yet been decidedly beneficial so far as the upholstery and dress of the period are concerned. So it would be hard, indeed, if, except in a joke, such a fireplace as Mrs. Forrester’s and such a coiffure as Lady Tompkins’s were laid to their charge. It would be harder still if the affectations of art were supposed to bring about such rude inhospitality as Mrs. Forrester, guided by her mother, shows to her husband’s old friend Colonel Woodd. All is fair, however, in the comedy of satire so long as it causes innocent laughter. And we laugh heartily and harmlessly as the fun goes merrily on. The awkward danger involved in Mr. Fisher’s acquaintance with Mrs. Blyth is skated over safely; the American Colonel, who sees through the whole situation, explodes it by a series of discoveries ingeniously altered from their parallels in the original. Streyke and Basil Giorgione are made to look as foolish as possible, and their dupe returns to her proper allegiance just in time to save herself from the consequences of her folly. Mr. Burnand’s sparkling dialogue, which is really full of good things, keeps up the spirit to the last, and the laugh does not die out until the fall of the curtain. The interpretation of the chief parts is better in intention than in execution, except so far as Mr. Coghlan’s stolid and manly Colonel is concerned. He, indeed, makes his dry jokes with fitting ease and absence of apparent intention; for the rest, effort at comic effect is too generally palpable. Mr. Fernandez makes Streyke a ludicrously repulsive creature, and Mr. Rowland Buckstone lacks natural aptitude for the parody of a Basil Giorgione. Miss Myra Holme’s grave manner suits well the illustration of one phase of the nineteenth century damozel’s character; she is “intense,” but we fear she is not sufficiently “willowy.” Lady Tompkins’s absurdities are duly emphasised by Mrs. Leigh Murray; Miss Amy Roselle is a bright representative of the pleasure-loving widow, and Mr. W. Herbert deserves high praise for the good taste and good judgment which enable him to retain sympathy for Forrester under somewhat difficult circumstances.

Saturday, 12 February 1881,

THE PLAYHOUSES.

Mr. William Gilbert, the father of Mr. W. S. Gilbert, the satiric poet and dramatist, once wrote a sociological romance — and an excellent one it was — called “A Story for the Philistines.” On Wednesday, the Second inst., just after last week’s “Playhouses” had gone to press, I went to the Prince of Wales’s Theatre to witness the first performance of what I may term a Grand Play for the Philistines, being a new comedy in Three Acts, entitled “The Colonel.” It is written by Mr. F. C. Burnand; its dialogue overbrims with fun and epigram; it is excellently well acted; it was recieved throughout with shouts of laughter and applause; and it must be pronounced a brilliant and unqualified success. It is earnestly to be hoped that the Philistine Host will so flock into the house of which Mr. Edgar Bruce is the lessee and manager for so many weeks as shall constitute a turning-point in the fortunes of a most charming and well-conducted theatre. Otherwise I hold “The Colonel” to be a very unfair play; and I am going to show its unfairness, and to protest against it.

Mr. Burnand has had the modesty to announce that “The Colonel” is partly founded on a French piece called “Le Mari à la Campagne,” which was adapted to the English stage many years ago by the late Mr. Morris Barnett as a comedy-drama called “The Serious Family.” The French author of “Le Mari à la Campagne” was less candid than Mr. Burnand. He did not mention his indebtedness to a short story called “Un Double Ménage,” any more than M. Alexandre Dumas the Younger mentioned that he had borrowed largely from the same Henri de Balzac’ of Coralie in “Un Grand Homme de Province à Paris,” in order to strengthen the character of Marguerite Gautier in his own “ Dame aux Camellias.” But let that pass. Everybody has stolen from Balzac. As a matter of fact, Mr. Burnand’s debt to the French dramaturge is infinitesimal; and more than nine tenths of “The Colonel” must be acknowledged as altogether original and redolent of the humour and vivacity of its accomplished author. As regards “The Serious Family,” it may be said absolutely that Mr. Burnand “owes the cat no fur,” and “the worm no silk.” His hypocrite is entirely out of diapason with the fraudulent and sanctimonious hypocrite Aminadab Sleek, who reminded us equally of Tartuffe, Mawworm, and the Rev. Mr. Stiggins. In lieu of a pseudo religious “fraud” it has pleased Mr. Burnand to devise an æsthetic one. He has invented a High Art swindler: a type of humanity, I confess, new to me. I have heard of roguish picture-dealers; but I never yet came upon a lecturer on the Beautiful in Art who was a mean and truckling rascal. Perhaps Mr. Burnand had “Janus Weathercock”–Wainwright the artist, and critic, and forger, in his eye when he drew the character of the despicable impostor Lambert Streyke. But, then, Wainwright was not a “mean cuss.” He did things en grand. He not only forged, but murdered.

The plot of “The Colonel” may be very briefly related. The once-happy home of Richard Forrester (Mr. W. Herbert) is made miserable by the invasion thereof by a rascally Professor of the Beautiful (with a big B), Mr. Lambert Streyke (Mr. James Fernandez), who contrives to breed a coolness between Forrester and his young, beauteous, and somewhat weak-minded wife (Miss Myra Holme), and utterly to fascinate and dominate her vulgar and foolish mother, Lady Tompkins (Mrs. Leigh Murray), the relict of a City Alderman. The crafty Streyke hopes to inveigle the widow, who is wealthy, into marrying him; and he is also eager to secure the hand of Nellie, Forrester’s sister and ward (Miss C. Grahame), for his nephew Basil Giorgione (Mr. Rowland Buckstone), whose real name is Bill Something or another, and who has been a druggist’s assistant, but who, at the instigation of his uncle, poses as an artist of the “consummate” kind, and paints horrible daubs which Streyke declares and the two infatuated women believe to surpass the masterpieces of Cimabue and Giotto. The results from this state of things are those which, in analogous circumstances, take place in “Le Mari à la Campagne” and in “Un Double Ménage.” Denied happiness at home, Forrester seeks it elsewhere. He is continually going on pretended fishing excursions; but his angling really means his putting up at a West-End hotel, assuming the name of Fisher, and carrying on a flirtation with a dashing and coquettish widow, Mrs. Blyth (Miss Amy Roselle). He even seems to be on the point of offering marriage to this lady, but Mr. Burnand dexterously slurs over such an embarrassing conjuncture; and the discovery of the pseudo Fisher’s escapade by the indignant Lady Tompkins and her daughter Olive timeously puts a stop to a very equivocal state of things so far as the relations of Forrester and Mrs. Blyth are concerned. The Deus ex Machinâ, who eventually sets things straight and restores peace and happiness to a distracted household, is a certain Colonel Woottwweel W. Wood (Mr. Coghlan), described as of “The United States Cavalry.” The Colonel, who is a friend of Forrester’s youth, kindly yet gravely remonstrates with him on the score of his compromising flirtation with the dashing widow, who he has not the slightest idea is an old and fondly-loved flame of his own. He discovers that the Professor of the Beautiful (with a big B) and his “consummate” nephew are arrant knaves and cheats, that, while pretending to be ascetics as well as “æsthetics,” scorning the flesh-pots of Egypt, they are gross Sybarites, who gorge heavy suppers at the house of one Romelli, an Italian restaurateur, with whom they have run up a long bill. “The Colonel” completely succeeds in unmasking this brace of impostors, and they are duly kicked out of Forrester’s house. The estranged husband and wife are reconciled; Lady Tompkins repents (the idea of a repentant mother-in-law is good); Nellie Forrester, instead of wedding young “Pill-blister” Basil Giorgione, is united to the real sweetheart of her choice, Edward Langton (Mr. Eric Bayley); and “The Colonel” is married to his old flame, Mrs. Blyth, to whom he has been all along passionately attached. Whether the moral of all this is that it is a wicked thing to go to the Grosvenor Gallery, and that the demons of Fraud and Hypocrisy are always crouching behind the canvases of Mr. E. Burne Jones and Mr. Walter Crane, I do not know.

Mr. Burnand’s funny ridicule of the people of culture who are called “Æsthetes” has been called by some critics harmless and good-natured. I am willing to believe in its harmlessness; because culture (or “cultchah,” as Mr. Burnand would call it) is rapidly making progress and will win the day over stupid and vulgar Philistinism; but I fail to see its good-nature. The costume worn and the phraseology assumed by a very small section of the party of culture may be legitimate subjects for ridicule. So, precisely, might be some of the histrionic fantasies of the Ritualists; but I distinctly question the right of a dramatist to invite inference that the love of an influential body of thoughtful and accomplished persons for mediæval art, or of a large number of earnest and devoted clergymen for mediæval rites and ceremonies can be made a cloak for the most detestable hypocrisy and for downright swindling. Because we may happen to admire Pietro Perugono or Andrea Mantegna, is there any need that we should forthwith go out picking pockets? Does the study of Pugin and the “Tracts for the Times” necessarily lead to our telling lies and obtaining money under false pretences? As rather an elderly hand at discovering the “tricks and manners” of dramatists, I think I can hit upon the cause of this gross injustice having been done to a most inoffensive class in English Society. In the first instance, Mr. Burnand (who is bound to back up the Maudle and Postlethwaytisms of Mr. Du Maurier) burned to have a slap at the “Æsthetes,” and he did not exactly know where to “have” them. The “Æsthetes” were to him even as the celebrated “Pump and Tubs” were for Mr. Vincent Crummles. On the other hand, Mr. Burnand found the plot of a play with a hypocrite in it. He would not make him a religious hypocrite, because he remembered and wished to avoid all kind of foregathering with Aminadab Sleek. So he took a couple of the coarsest rascals on whom he could lay hands — two more squalid caitiffs never footed it on the treadmill — and draped them with the garments of an æsthetic professor and a “consummate” painter. But the clothes do not suit their limbs, and I protest against the misfit. The piece in its dialogue and costumes is so clever, and the acting is, “all round,” so good, that I shall go to see “The Colonel” again, and report further upon it next week. For the sake of the Philistines (if there be geese there must be stubble), I hope that “The Colonel” will have a long and prosperous run.

[The final paragraph of the article deals with “Messrs. Tom Taylor and Charles Reade’s original comedy of ‘Masks and Faces’ ... revived” at the Haymarket Theatre, Feb. 5, 1881]

G. A. S.

Saturday, 19 February 1881, p. 81.

“THE COLONEL” IN A NUT-SHELL.

A Philistine and Maudle visit the Prince of Wales’s.

I WENT to see The Colonel at the Prince of Wales’s, and I took MAUDLE with me. I had some trouble in persuading him to accompany me, for at first he  flatly refused to go to any theatre but the Lyceum, but at last he consented. Then another difficulty arose, — should he take his lily with him. I had heard something about the play, so I said decidedly not, and consoling himself with the reflection that the night air might not agree with the “precious” things, and bidding it an affectionate adieu, we set out for Mr. EDGAR BRUCE’S Theatre in Tottenham Street.

flatly refused to go to any theatre but the Lyceum, but at last he consented. Then another difficulty arose, — should he take his lily with him. I had heard something about the play, so I said decidedly not, and consoling himself with the reflection that the night air might not agree with the “precious” things, and bidding it an affectionate adieu, we set out for Mr. EDGAR BRUCE’S Theatre in Tottenham Street.

Here is the story of the play. A Mr. Forrester, physically strong, but morally weak, is married to a charming wife. But, unhappily, that lady, under the guidance of her mother, Lady Tompkins, has fallen a victim to Æstheticism. So Forrester’s house is decorated according to the prevailing mania, with hangings in “art-colours” and sunflowers, plates and pottery, and mediæval furniture;  his wife and mother-in-law appear as “arrangements in brick-red and sage-green, and even attire his poor little sister in peacock-blue, while they religiously endeavour to life up to their hawthorn china. And that is not all. The presiding genius of the house is a Professor of Æsthetics, a certain Lambert Streyke, who is, to the eyes of all but his dupes, a ghastly old humbug; while with him is his nephew, Basil Giorgoine , once a chemist’s assistant, but now a painter. B. G. has executed a work of art, which hangs in the place of honour, and I can only say it is so deliciously like the anatomical curiosities of Mr. BURNE-JONES, that it ought to be secured at all hazards, for the Grosvenor Gallery. This “Arrangement in Gold” is, I have heard, the work of a rising young artist — Mr. PADGETT — not an Æsthete. When we saw all this on the stage MAUDLE was delighted; he echoed the language of the play, declared it was “quite too utter,” and regretted he had not brought his lily. Meanwhile, we saw poor Forrester’s misery, when, to his great joy, in comes his old friend Colonel Wood, of the U.S. Cavalry, and this gentleman at once sees how the land lies, sums up Mr. Streyke in an instant, and determines ot save his friend from this intolerable bondage. At first, however, victory remains with Mr. Streyke and his infatuated disciples,

his wife and mother-in-law appear as “arrangements in brick-red and sage-green, and even attire his poor little sister in peacock-blue, while they religiously endeavour to life up to their hawthorn china. And that is not all. The presiding genius of the house is a Professor of Æsthetics, a certain Lambert Streyke, who is, to the eyes of all but his dupes, a ghastly old humbug; while with him is his nephew, Basil Giorgoine , once a chemist’s assistant, but now a painter. B. G. has executed a work of art, which hangs in the place of honour, and I can only say it is so deliciously like the anatomical curiosities of Mr. BURNE-JONES, that it ought to be secured at all hazards, for the Grosvenor Gallery. This “Arrangement in Gold” is, I have heard, the work of a rising young artist — Mr. PADGETT — not an Æsthete. When we saw all this on the stage MAUDLE was delighted; he echoed the language of the play, declared it was “quite too utter,” and regretted he had not brought his lily. Meanwhile, we saw poor Forrester’s misery, when, to his great joy, in comes his old friend Colonel Wood, of the U.S. Cavalry, and this gentleman at once sees how the land lies, sums up Mr. Streyke in an instant, and determines ot save his friend from this intolerable bondage. At first, however, victory remains with Mr. Streyke and his infatuated disciples,  for while Forrester is very anxious that his friend should stay with him, Lady Tompkins determines to get rid of the Philistine, and the obedient wife, though sorely against her will, allows the Colonel to be sent to an hotel. So ends the First Act in which the tone of Æsthetic society is preserved with such satirical fidelity that it made me shudder and delighted MAUDLE, who wildly proposed “two lilies and a split soda,” if that refreshment were attainable: which, happily, was not the case.

for while Forrester is very anxious that his friend should stay with him, Lady Tompkins determines to get rid of the Philistine, and the obedient wife, though sorely against her will, allows the Colonel to be sent to an hotel. So ends the First Act in which the tone of Æsthetic society is preserved with such satirical fidelity that it made me shudder and delighted MAUDLE, who wildly proposed “two lilies and a split soda,” if that refreshment were attainable: which, happily, was not the case.

In the Second Act we are in a very different atmosphere. Here, on a fourth floor flat, furnished with a total disregard for Æsthetic principles,  lives pretty Mrs. Blyth, a gay widow, who wins all hearts, and with whom we discover that Mr. Forrester, calling himself Fisher, is flirting outrageously. He introduces the Colonel to Mrs. Blyth, and it turns out they are old lovers separated through a misunderstanding; and it was, indeed, to seek out the lady that the American came to Europe. Then occurs an alarming complication. Mrs. Forrester arrives to enlist Mrs. Blyth’s co-operation in an Æsthetic scheme, is followed by her mother and Mr. Streyke, and discovers her husband, whom she had supposed to have started for the country, and the Act winds up on a telling situation.

lives pretty Mrs. Blyth, a gay widow, who wins all hearts, and with whom we discover that Mr. Forrester, calling himself Fisher, is flirting outrageously. He introduces the Colonel to Mrs. Blyth, and it turns out they are old lovers separated through a misunderstanding; and it was, indeed, to seek out the lady that the American came to Europe. Then occurs an alarming complication. Mrs. Forrester arrives to enlist Mrs. Blyth’s co-operation in an Æsthetic scheme, is followed by her mother and Mr. Streyke, and discovers her husband, whom she had supposed to have started for the country, and the Act winds up on a telling situation.

Third Act. Streyke and his nephew fall out, and we hear of a bill run up by the pair for all sort of luxuries at a neighbouring restaurant, while they pretend to live on the contemplation of lilies. Mrs. Forrester has appealed to the Colonel, who hoists Streyke with his own petard, opens Lady Tompkins’s eyes, reconciles husband and wife, is accepted by Mrs. Blyth, arranges an impromptu carpet dance after the fashion of an American “Surprise,” when the ladies return to the garments of civilisation, and the play winds up merrily with the discomfiture of the Æsthete, and the triumph of common sense.

Maudle was and is very angry. He sat in sulky silence until the end, and then the inextinguishable laughter roused him into speech. He said he considered the Author a person of no culture, a Philistine of the Philistines, wholly destitute of sweetness and light and of any feeling for what is most precious in Art. I have shown this to MAUDLE, who admits it is a fair account of the piece, but adds, that he wonders the brain did not curdle within the cranium of the perpetrator of such an outrage. As he quitted the theatre he sighed out, “We are not all Impostors.” I at once admitted the truth of this remark, as certainly MAUDLE ought to know of some exceptions. Then he glided homewards, and comforted himself with cold lily and Mr. PATER.

The acting is admirable. Mrs. LEIGH MURRAY and Miss MYRA HOLME, as Lady Tompkins and Mrs. Forrester, have caught the postures and trick of speech of the School to the life; while Miss AMY ROSELLE’S Mrs. Blyth, and Miss GRAHAME’S Nellie, were bright and pleasant performances. Mr. COGHLAN’S Colonel is a masterly performance: he shows us an American gentleman, not a vulgar caricature of a soldier in the U.S. Army, and gave every line with telling effect. Mr. FERNANDEZ created a Streyke out of his own inner consciousness, which made MAUDLE wild. Mr. ROWLAND BUCKSTONE was amusing as Basil Giorgione; while Mr. HERBERT was a fresh manly representative of Mr. Forrester .

Mr. BRUCE SMITH’S Æsthetic interiors are of a truth “consummately precious,” and the Æsthetes, on the whole seemed to have rather the best of it in dress and decoration. That, indeed, was MAUDLE’S opinion, and I am bound to believe him, though I am only

A PHILISTINE.

[vol. 78,] March 26, 1881,

SKETCHES AT THE PRINCE OF WALES’S THEATRE.

It is very seldom that English dramatists in the selection of their subjects embody the very spirit and essence of the times, and use their position to satirise the follies or the vices of society. The French are very fond of doing it; and of recent years, Alexandre Dumas and Victorien Sardou have given the world no work that is not flavoured with the subject-matter of everyday controversy. Dangerous, no doubt, and extremely delicate is the task that the stage satirist sets himself when he uses the theatre as his platform; and it is possible that the Examiner of stage plays might object to pass the kind of ridicule that was ready and easy of application. On one occasion he did forbid a translated French work destined to prove that female luxury led to immorality. “The Happy Land,” no doubt, was a successful satire, though in that case costume and caricature of living statesmen were necessary to give it point; and “Diplomacy” directly touched upon the complications arising out of the Eastern Question. The success of Mr. Burnand’s “Colonel” will probably give rise to many more bright and amusing social satires; though in such cases a light hand is essential, and good nature imperative.

The affectations of æstheticism as practised in certain art-circles is the keynote of the humorous idea. Mr. Du Maurier, in Punch, was the first to tilt good-naturedly at this society conceit; Mr. Maudle and Mr. Postlethwaite became as well known to Punch readers of to-day as our old friends Mr. Biggs, Mrs. Caudle, or Mr. and Mrs. Naggleton, and the worship of the lily and the sunflower was instantly a subject for persistent banter. It is a question whether the satire was not a little premature. The world is large, and the more brainless of the æsthetic school are in a miserable minority; the art-jargon considered so exquisitely funny to some is Greek to all but the artistically initiated, and there was always the danger that, in ridiculing the brainless and affected, it was possible to throw cold water on an intellectual movement that has brought beauty and good taste to our homes in thousands of decorative designs and an improved style of what may be fairly called Victorian architecture. But Mr. Du Maurier could not resist laughing at the effeminate men who could “lunch on a lily,” or the wan and wasted women who dreamed of “living up to a china tea-pot;” and Mr. Burnand, with an equally strong sense of humour, through in a different direction, thought he would follow it up in action on the stage.

He remembered an old French play, the “Mari à la Campagne,” which had done good service on the stage as “A Serious Family.” It was a witty satire on hypocrisy. A Chadband or Stiggins had got influence of the the female portion of a family, and the puritanical element was so distasteful to the husband that he was driven to evil courses thereby, from which he was only rescued by repentance and promises of amendment all round. Mr. Burnand conceived that Dick Forrester, a young fellow who sincerely loves his pretty wife, can be driven away from home disgusted at sad-coloured walls, lilies in blue jars, sunflowers in Dunmore pottery, and a rampant form of aggressive æstheticism. The house is taken possession of by the apostle of the school, one Lambert Streyke, who is a ready talker, but an arch-impostor; and matters go so far that an old American friend of Dick Forrester’s, one Colonel Wood, is turned out of the æsthetic house because he is an unbeliever and a Philistine. Dick may have some excuse, but his conduct is not without suspicion. When he pretends to go on fishing excursions he is flirting with pretty widows as an unmarried man; but the Colonel, who has loved the pretty widow long ago, is the deus ex mâchina who reconciles the silly young husband and wife, banishes the impostors, and, wonder of wonders, converts a home in which a certain phase of art had some footing, into a nest of determined and arrogant Philistinism — in other words, unredeemed vulgarity. The types selected by our artist are easily recognised. One of the prettiest attitudes in the play is when Dick Forrester takes his wife into his arms, both promising mutual amendment and good faith, though the poor lady is condemned to voyant unbecoming dresses, instead of the gold robe and emerald hat that so suits the Veronese tresses of Miss Myra Holme. Naturally we have Basil Giorgione (Mr. Rowland Buckstone), the nephew of the art-impostor, adoring a lily in a glass, and Lambert Streyke (Mr. Flockton), the poetaster, shaking his fist, tearing his hair, and bewailing the fate of his undelivered lecture. The she-dragon of all witty comedies is the mother-in-law, and she is embodied by Lady Tompkins, who, seated at a table in a rapt attitude, gazes on a sunflower. The gay and gushing Nellie, tomboy in manner and Philstine at heart, who looks charmingly as represented by Miss C. Grahame, but insists that “she looks like one of Marcus Ward’s Christmas cards,” and is chaffed by the street boys, completes the æsthetic circle. Philistinism on our artist’s pictures boasts the famous Colonel, played to perfection by Mr. Coghlan, with a reserve, a quiet, and a polished decision quite new to the English stage; and Mrs Blythe, the merry widow, who is enchantingly represented by Miss Amy Roselle. “Have you seen his “Pan by the River?’” moans out Mrs. Forrester to her unæsthetic friend the widow, meaning a poet and his masterpiece. The way in which Miss Roselle caps the question with “What!” is one of the funniest moments of this witty play. Opinions differ as to its necessity and motive; but that it makes crowded audiences roar with laughter there can be no question.

The little cleverly-written play by Sydney Grundy called “In Honour Bound” is borrowed form one solitary idea in Scribe’s comedy “Une Chaine,” and shows how necessary it is for young ladies to burn their love-letters, whether married or single. They do not always find such trusting and honourable men as Sir George Carlyon (Edgar Bruce), who, like a good fellow, burns the record of his wife’s weakness, and earns her love.

C. S.

The Illustrated London News, March 26, 1881, p. 301

London: Reeves & Turner, 1882, third edition, pp. 91-94.

After Mr. Du Maurier had pretty well used up the subject of the Aesthetic School in a somewhat impersonal and not unkindly manner, the editor [F.C. Burnand] took up the topic, and having a French play (Le Mari a la Campagne) to work on as a foundation, he borrowed some good situations from an old play entitled "The Serious Family," and by making "The Colonel" an American, with a Yankee twang (a character which entirely depends for its success upon the actor who represents it), with-the witty remark, "Why, cert'nly," to be repeated ad libitum and ad nauseam, he manufactured a play, which (after some difficulty with incredulous managers) was produced, and owing to the popular interest in AEstheticism, obtained a success its own intrinsic merits would never have obtained for it.

The history of The Colonel is peculiar. On Monday, the third of June, 1844, a new comedy in three acts was produced at the Theatre Francais, Paris, entitled Le Mari a la Campagne.

This amusing piece (written by Messrs. Bayard and J. De Wailly) proved a success, and naturally it attracted the attention of English managers. It was admirably translated by Mr. Morris Barnett, and under the title of The Serious Family, was produced at the Haymarket Theatre in 1849, when the late J. B. Buckstone performed the part of the canting hypocrite Aminadab Sleek, upon which character Mr. Burnand modelled his Lambert Streyke. In fact, in reading The Serious Family one cannot but be struck with the audacity of the production of The Colonel as an original piece; scene for scene, in some instances word for word, does Mr. Burnand follow Mr. Barnett. The leading motive only is altered; in the original the hero is driven from home by the melancholy puritanical nature of his surroundings, a very probable assumption, whereas in The Colonel the same result is brought about by the Aesthetic mania of the hero's wife and mother-in-law, which is an absurdity, for Aestheticism cannot but tend to beautify a home and render it more attractive to its occupants. Here is a comparison of the casts of the two plays: | [92]

The characters in Mr. Morris Barnett's, The Serious Family, 1849:

Charles Torrens.

Captain Murphy Maguire (an Irish-man)

Frank Vincent.

Aminadab Sleek.

Danvers.

Lady Creamly.

Mrs. C. Torrens.

Emma Torrens.

Mrs. Delmaine.

Graham (her maid).

Their counterparts in Mr. Burnand's original comedy, The Colonel, 1881:

Richard Forrester.

Colonel W. W. Woodd (a Yankee).

Edward Langton.

Lambert Streyke.

Lady Tompkins.

Mrs. Forrester.

Nellie Forrester.

Mrs. Blyth.

Goodall (her maid).

*Basil Giorgione (Streyke's nephew).*

[* A small part created by Mr. Burnand. The other characters are simply re-named, the amusing Irish Captain of the original being transformed into the Yankee Colonel.]

Here is an American notice of it taken from Puck of last January:

"'The Colonel,' at Abbey's Park Theatre, was a great disappointment to everybody. Not that Mr. Wallack is to blame, for he does what is expected of him; but the play is nothing more than an unblushing appropriation of another man's work. The French original, 'le Mari a la Campagne,' is, of course, at everybody's service, but the author of 'The Serious Family' exhausted its possibilities for the English-speaking stage in the best manner. It is, then, rather cool, to say the least of it, for Mr. F. C. Burnand, the editor of our venerable and funereal contemporary, Punch, to call 'The Colonel' his play, when he has simply altered the dialogue, here and there, of another play, and made impossible aesthetes of what, in the original, were possible religious enthusiasts. Mr. Burnand, in spite of his reputation, by this work can certainly lay no claim to be considered either a wit or a playwright, and his ideas of dramatic construction are evidently of the crudest and most conventional character. 'Why, certn'ly,' repeated at intervals, is not sufficient to make an original play, although Mr. Burnand thinks that it is. The scenery was good, and the acting, as a whole indifferent, although Miss Rachel Sanger played her part in an attractive manner. The British importations who took the other characters did not impress us by their finish or excellence."

But how plainly do these American writers show their small knowledge of English character in writing thus. | [93] What does the British public care for the intrinsic merit of a poem, a picture or a play-if Royalty does but single it out for a passing word of recognition, its name is made, and the poet, artist, actress, playwright, or music-hall singer, at once becomes famous. So with The Colonel, what was most vaunted in its enormous and ubiquitous advertisements? Its originality-No! Its comicality- No! Its truth to nature-No!:- Mr. Burnand and Mr. Edgar Bruce knew which was their trump card, and they played it, thus :

"THE COLONEL." By F. C. BURNAND.

MR. EDGAR BRUCE, at the invitation of their Royal Highnesses the PRINCE and PRINCESS of WALES, gave a Special Representation of "THE COLONEL," with his Company, at Abergeldie Castle, on TUESDAY, OCTOBER 4th, 1881. The Performance was honoured by the gracious presence of

HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN,

THEIR ROYAL HIGHNESSES THE

Prince and Princess of Wales, Princess Louise, Princess Beatrice, &:c., &:c.

Few among all those who profess to know everything about Maudle and Postlethwaite, who laughed at The Colonel and Patience can honestly say they knew anything about Aestheticism before it was made the target of our sneering satirists. The secret of the situation and the reason why it is profitable, lies in the fact that aesthetes are supposed to belong to the "Upper Crust." One of the characteristics of the lower middle classes is an intense desire to know, or to profess to know all that goes on in aristocratic circles. A good thing it is for our national reputation that our English comic writing and English comic draughtsmanship have a history beyond the only one that can be found for them in the latter part of the nineteenth century, else these things would be merely comic by means of their audacious pretences upon comicality. As it is, even this sort of literary and artistic ware has its imitators. The only thing which reconciles one to Punch is that one can generally understand his aims if one cannot always respect his motives. Very | [94] different is it with the inferior article. Providence alone knows what is meant by either type or wood blocks in two other so-called comic papers, which are never in the least comic unless unintentionally, as when they attempt to prophecy before they know.

One of these professes to be a staunch Tory journal; the other is as decidedly Liberal. Yet both are owned by one and the same firm, and what is still more curious is, that at times these two politically antagonistic organs have been edited by one and the same editor. So much for the political consistency of our comic journals.

London: Elek, 1969, pp.115-6.

[Chapter 6 Satire and Comment]

F. C. Burnand (1836-1917) became the editor of Punch at the height of its campaign of ridicule aimed at art in general and aesthetes in particular. Realizing that the subject was still popular with the public he wrote a play or, to be more precise, converted an existing French one, in which the aesthetic characters were represented not only as fools but as knaves. The joke would seem to have failed to some extent because the sets and costumes, at which the audience were expected to laugh, were so attractive that several critics regarded the play The Colonel as an excellent advertisement for aestheticism.

After seeing the play E. W. Godwin wrote that the set 'presented to us as wrong, we find is furnished with artistic and simple things; a charming cabinet in walnut designed by Mr Padgett for the green room, some simple inexpensive Sussex chairs like those sold by Messrs W. Morris and Co., a black coffee table after the well known example originally designed in 1867 by the writer of these notes; a quite simple writing table, matting on the floor, a green and yellow paper on the walls, a sunflower frieze, a Japanese treatment of the ceiling and a red sun such as we see in Japanese books, and a hand screen, make up a scene which if found wanting in certain details and forced in sunflowers, is certainly an intriguing room with individuality about it, quiet in tone and what is most important, harmonious and pleasing.' [The British Architect, vol.xv, 1881, p.379.] He also reported seeing the leading lady outside the theatre where she passed unnoticed though 'her private costume was modelled line for line on that she had just worn as an aesthete in the comedy, and which the audience had been invited to ridicule'.

This view of The Colonel was taken by other and presumably more detached commentators such as the dramatic critic of The London Illustrated News whose enthusiasm was such that he visited the play twice in the first month of its production, February 1881, and wrote about it at length on both occasions. He thought the plot trivial but found the performance excellent and the settings and costumes the best that had been seen on the London stage for many years. This anonymous critic, not unnaturally, took exception to the suggestion implicit in the play that an admiration for the work of the artists of the Italian Renaissance automatically led to the picking of pockets or the telling of lies. He was, however, delighted by the subtle education of the Philistines who came all unsuspecting to enjoy a gay evening in the theatre little thinking that they were absorbing the philosophy at which they were laughing. The critic felt that the whole thing was quite harmless because in his view culture was rapidly winning the day 'over stupid and vulgar Philistinism'.

The play had a long and successful run in London and in the autumn of 1881 gained the distinction of a Royal Command performance before Queen Victoria at Abergeldie Castle in Scotland. The new ideas were so generally accepted by this time that it was reported that furniture for the aesthetic scene was purchased expressly in Edinburgh to save the cost of transport from London and additional pieces were borrowed from the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Oxford: Phaidon, 1996, p.119.

F.C. Burnand, sensing a theatrical bonanza, opened The Colonel at the Prince of Wales Theatre in February 1881, just two months before the smash hit of the year dealing with the same theme, Patience. A few months later The Colonel achieved the ultimate Victorian accolade of success, royal approval, in what might be described as the strange story of how Queen Victoria was amused.

In 1881 Queen Victoria was staying as usual at Balmoral for the summer. Within driving distance was Abergeldie Castle, which since his marriage the Prince of Wales had made his home during the grouse-shooting season. Twenty years had passed since the demise of Albert, the Prince Consort, and at last the Queen was persuaded that a little light might penetrate the gloom of her widowhood and was encouraged to visit Abergeldie Castle for the evening to attend a theatrical command performance. The curtain rose. On to the stage came the figure of Lambert Stryke, a thinly veiled caricature of the young Oscar Wilde. Stryke's opening speech set the tone for the rest of the play:

The object which the Aesthetic High Art Company, Limited, has in view is the cultivation of The Ideal as the consummate embodiment of The Real, and to proclaim aloud to a dull, material world the worship of the Lily and the Peacock's Feather. (Exclamations from the rest of the cast - 'Perfect', 'Too Precious', 'Consummate'!)

The Queen's own able pen takes up the story:

The piece given was The Colonel in three acts, a very clever play, written to quiz and ridicule the foolish aesthetic people who dress in such an absurd manner, with loose garments, large puffed sleeves, great hats, and carrying peacock's feathers, sunflowers and lilies. It was very well acted, and strange to say, most of the actors are gentlemen by birth, who have taken to the stage as a profession. It was the first time I had seen professionals act a regular play since March '61. We got home shortly before twelve, having been very much amused ...

Not only the Queen was amused. The play had already run in London for over six months, and several touring companies were on the road, including the one that performed that evening. Its success was to continue. 'It ran, ran, ran. Over a year!' as Burnand noted with great satisfaction in his memoirs. Unlike Patience, however, its fame has not survived, for it lacked both Gilbert's wit and Sullivan's music.