| THE COLONEL |

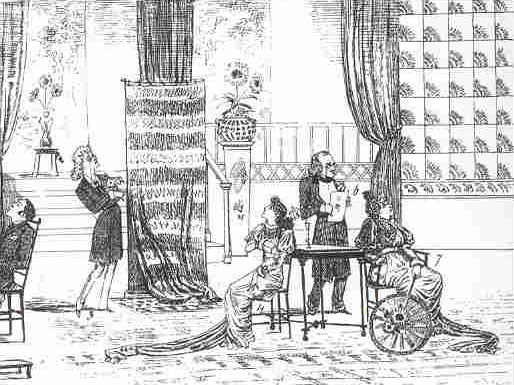

| Scene from The Colonel, from The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News (19 February 1881):

Tertiary colours, ebonised spindly furniture, rugs, Japanese paper fans, lilies in long-necked vases and sunflowers abound. Most important of all – the dado! |

Much of the success of The Colonel was owing to the stage sets created with advice from George Du Maurier, who wrote to Burnand:

Try & have a room papered with Morris' green Daisy, with a dado six feet high of green-blue serge in folds - and a matting with rugs for floor (Indian red matting if possible), spider-legged black tables & sideboard, – black rush-bottomed chairs and arm chairs; blue china plates on the wall with plenty of space between - here and there a blue china vase with an enormous hawthorn or almond blossom sprig ... also on mantelpiece pots with lilies & peacock feathers - plain dull yellow curtains lined with dull blue for windows if wanted. Japanese sixpenny fans now & then on the walls in picturesque unexpectedness. (Lionel Lambourne, The Aesthetic Movement, Oxford: Phaidon, 1996, p. 121.)

The stage-set of The Colonel was bound to be a pastiche of the work of E.W. Godwin, 'the First of the Aesthetes' (Lambourne, p. 153). He was renowned as the architect of the White House (1877) for James Abbott McNeill Whistler and a studio, known as Keats House (1878), for Frank Miles (1852-91), both on Tite Street, Chelsea. It was easy to lampoon his austere, spindly-Japanese style. Godwin was no Morris, his furniture being manufactured commercially, principally by the cabinet-maker William Watt. A lavish catalogue was issued in 1877 dedicated to Princess Louise, the Queen's most artistic daughter, which included his distinctive eight-legged spidery table. There were plenty of distinctive pieces for Bruce Smith, the set-designer as specified on the programme, to purloin. In his well-known leader in The British Architect, Godwin quite rightly reveals some bitterness:

the set presented to us as wrong, we find is furnished with artistic and simple things; a charming cabinet in walnut designed by Mr Padgett for the green room, some simple inexpensive Sussex chairs like those sold by Messrs W. Morris and Co., a black coffee table after the well known example originally designed in 1867 by the writer of these notes; a quite simple writing table, matting on the floor, a green and yellow paper on the walls, a sunflower frieze, a Japanese treatment of the ceiling and a red sun such as we see in Japanese books, and a hand screen, make up a scene which if found wanting in certain details and forced in sunflowers, is certainly an intriguing room with individuality about it, quiet in tone and what is most important, harmonious and pleasing.' (The British Architect, vol.xv, 1881, p.379)

Godwin also reported seeing the leading lady outside the theatre where she passed unnoticed though 'her private costume was modelled line for line on that she had just worn as an aesthete in the comedy, and which the audience had been invited to ridicule'.

Godwin had begun a close relationship with the Manchester-based magazine The British Architect, as the main leader writer and consultant, in 1877. He penned the leading article each week until mid-1879, in which he asserted the principle Aesthetic aims and beliefs. For example, in 1878 he declared: 'Hitherto we have rarely allowed ourselves to step beyond the professional limits of one art, but for the future we hope to take a wider range…we shall embrace in our survey the broader ground of painting and sculpture, taking note the while of that art which involves all others, namely the art of the stage…to work for greater harmony and unity of thought in the surroundings of modern life will be one of our aims'. (Lambourne, The Aesthetic Movement, p. 166)

Intensely interested in the theatre, partially due to his involvement with the great actress Ellen Terry, Godwin must have been galled at the sight of his style transposed to the stage. Godwin had first seen Ellen Terry on the stage in 1863, when she was only fourteen, but they did not elope until 1868. In between Ellen, then only sixteen, had married George Frederick Watts, 'England's Michelangelo', aged forty-six. The union did not last but the marriage was not dissolved until 1877. Godwin transformed their London home, in Taviton Street, into a model of Aesthetic taste: 'painted in a pale grey green (that green sometimes seen at the stem end of a pineapple leaf when the other end has faded)- Indeed I may as well confess that most of the colours in the rooms have been gathered from the pineapple' (Lambourne, p. 161). This is a good example of the excessive language aesthetes were prone to use.

Godwin was not modest about his work, waxing lyrically on his delicate colour schemes in true 'Paterian' style:

No description, however, except that which may be conveyed in the form of music, can give an idea of the tenderness and, if I may say so, the ultra-refinement of the delicate tones of colour which form the background to the few but unquestionable gems in this exquisitely sensitive room. I say sensitive for a room has a character that may influence for good or bad the many who may enter it, especially the very young. (Lambourne, p. 162)

There must have been quite a few who wished to see Godwin brought down a peg or two. By 1881 he was associated with the aesthetic interior both at home and on the stage.

In 1875 Mrs Bancroft, wife of the distinguished actor manager, offered Ellen Terry the role of Portia in a new production of The Merchant of Venice and Godwin the contract for designing the sets and costumes. A young Oscar Wilde, still an undergraduate at Oxford, was moved to compose a sonnet to Ellen after attending the first night,:

For in that gorgeous dress of beaten gold,

Which is more golden than then the golden sun,

No woman Veronese looked upon,

Was half so fair as thou whom I behold.

Godwin had designed the 'dress of beaten gold' but ironically the couple's seven-year relationship was at an end. They remained on friendly terms and Godwin continued to design costumes and sets for Ellen.

From this time Godwin's time was equally divided between theatrical design and architecture, his designs being acclaimed by the famous actor manager Beerbohm Tree as marking: 'the Renaissance of theatrical art in England'. One aspect of his design work, important in the context of The Colonel, is its archaeological correctness, as Mrs Blyth, a gay widow of two years 'who wins all hearts', declares she is not 'Archy':

Archaeological people amuse me. I call them 'Archys' for short- I won't have any of their cold greys and sad yellows in my decorations- there's nothing of the severe 'Archy' tone about me- I'm neither mediaevally nor classically Archy- I'd as soon be Noah's Arky at once.

Godwin's costumes and sets of The Merchant of Venice were closely based on Venetian originals. Godwin sent Ellen notes on her costume for Tennyson's The Cup at the Lyceum in 1880, in which she played a Greek priestess. He drew figures demonstrating attitudes, and dress, which were and were not archaeologically justified. Godwin had an expert knowledge of Greek costume.

Aesthetic dress, with its emphasis on drapery, was deeply indebted to historical prototypes. Edward Burne-Jones would deploy the Greek variant of softly clinging folds in his most famous aesthetic work, The Golden Stairs, shown at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1880. This painting has always been cited as the inspiration for Gilbert's chorus in Patience (1881). Both Whistler and Albert Moore opted for the Greco-Roman style, with Japanese undertones, during the 1870s. George Fleming (Constance Fletcher) asked her readers to imagine themselves as figures in a painting and dress themselves according to the rules of composition. Inspiration came from historical models, contemporary books, especially those illustrated by Walter Crane and Kate Greenaway, and paintings and people seen at the Grosvenor Gallery.

Many experts put pen to paper to offer their advice, including Charles Eastlake, Mrs Mary Eliza Haweis, George Fleming (Constance Fletcher) and Rosamund Marriott Watson. Mrs Haweis based her approach on a thorough understanding of historical costume, displaying the type of knowledge associated with connoisseurship. In The Art of Dress (1879), she recommended her readers to draw their sleeves and caps from Renaissance paintings. Mrs Haweis did not favour any specific period or style. As long as the outfit proved its wearer had studied old paintings, it did not matter which particular paintings inspired the outfit.

A series of sketches in The Queen, `Lady Students at the National Gallery' (1891), demonstrates aesthetic variety in dress, with each look named after the artist, or period, which had inspired it. This imitative approach was seen to be characteristically feminine, as given a woman's lack of creative powers she would naturally adopt a look created by a male artist. In effect, women were encouraged to enact painted images, giving currency to the woman who was a 'sort of live picture'. Aesthete dress was eventually reduced to a cliché, which approached a semi-monastic uniform. The Colonel and Patience popularised the stereo-type rather than the original works of art. Fancy Dresses Described or What to Wear at Fancy Dress Balls (1882) by Ardern Holt illustrated an outfit for an aesthetic maiden based on the lovesick chorus in Patience.

Clearly both the sets and the costumes contributed to the success of The Colonel. Evidently even 'select' artistic audiences were quite prepared to laugh at their own enthusiasms, while the critic of The London Illustrated News was 'delighted by the subtle education of the Philistines who came all unsuspecting to enjoy a gay evening in the theatre little thinking that they were absorbing the philosophy at which they were laughing'.

There is no doubt that the sets of The Colonel gave the general public a clear model to follow: tertiary colours, black-spindly furniture, rugs and long-necked vases containing single lilies or sunflowers. At its best the Aesthetic interior, Godwin style, was austere. In The Colonel it becomes cold and unwelcoming, alienating the head of the household. But, aided by stage productions, instructions manuals and lecture tours, Aesthetic décor was a commercial success, with the 1880s seeing the proliferations of 'artistic manufactures' from pottery and glass to embroidery and jewellery. Liberty's of Regent Street would cash in, selling art furniture and pottery, as well as Oriental goods. Aestheticism would pave the way for both the Arts and Crafts movement and Art Nouveau in the succeeding decade. Even in 1881 the new ideas were so generally accepted that 'it was reported that furniture for the Royal command performance at Abergeldie Castle was purchased expressly in Edinburgh to save the cost of transport from London and additional pieces were borrowed from the Prince and Princess of Wales'. It was this 'Royal Performance', according to Walter Hamilton, that guaranteed the success of the play.

© Anne Anderson, July 2004.